In this post I will be continuing my talk about Benford’s Law. Prior to this, I talked about what Benford’s Law was and gave an easy way to explain how it works. In this article, I will be talking about scale invariance and going deeper into why exactly Benford’s Law works.

If you have not read my first blog on Benford’s Law, read it here:

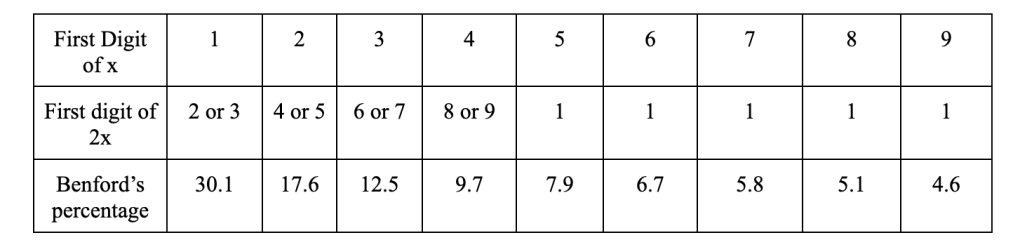

A very important part of Benford’s Law is that the pattern of numbers is independent of the units of measure. If a financial data set follows Benford’s Law in US Dollars, then it will do so in another currency, such as pounds. This property is called scale invariance. A simple way to look at the scale invariance of Benford’s Law is to look at how numbers behave when doubled. If a number begins with a 1, that number doubled will start with either a 2 or 3. If a number begins with a 2, that number doubled will start with either a 4 or 5 and so on. This is until we reach 5. After this, the numbers 5-9 doubled will all start with a 1. Here is a data table to further understand scale invariance:

If you add up the percentages of the numbers 5-9 (7.9, 6.7, 5.8, 5.1, 4.6) you get 30.1. When any number that begins with 5-9, the result will always be the starting number as one. 30.1 is Benford’s Percentage as shown on the data table. If we did this with any number instead of 2, such as pi, it would still follow Benford’s Law.

For many years, decades even, Benford’s Law was considered as a gimmick for magic shows or a quirk of data. This all changed in the nineties. A man named Ted Hill who was a professor at Georgia Tech, wanted to find a theoretical explanation of exactly why and how Benford’s Law worked. Ted Hill made a game out of his findings that I will first go into to explain.

In the game, Ted picks a number, and someone else picks a number (1-9). Then both numbers are multiplied together. If the number starts with 1, 2, or 3, Ted wins. If they do not (start with 4-9), then Ted loses. The game seems to be weighted in Ted’s opponents favor. But according to Benford’s Law, this is not true. This is because the number one will be the result 30.1% of the time. 2 would be 17.6% of the time; and 3 would be 12.5% of the time. These percentages add up to 60.2 percent. This means that Ted would win 60.2% of the time, meaning he would win more. This game illustrates the fundamental principle of Benford’s Law: the distribution of leading digits is not uniform, but rather follows a predictable pattern that is independent of the scale or units of measurement. This property of scale invariance underlies the widespread applicability and relevance of Benford’s Law in various and practically all fields, such as finance, economics, and data analysis.

Leave a comment